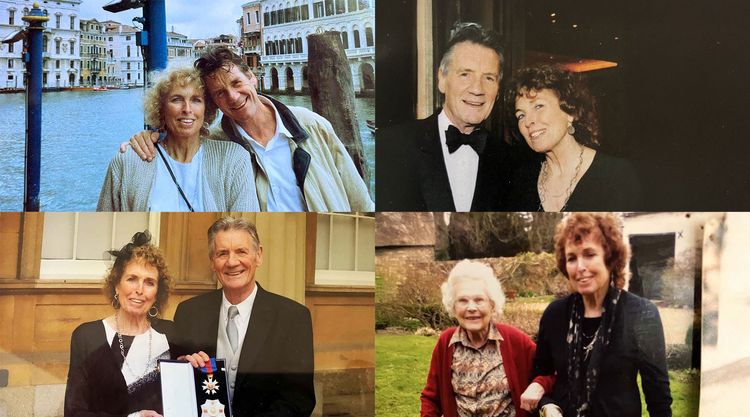

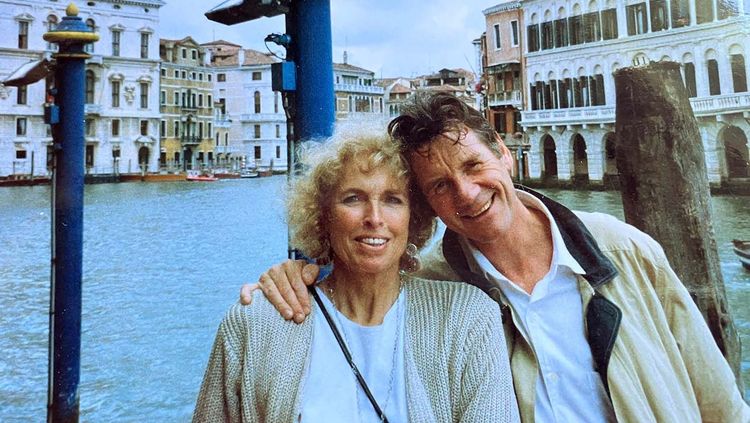

In the latest episode of On the Marie Curie Couch podcast, Sir Michael Palin talks with Jason Davidson about his wife, Helen, who died in 2023. Reflecting on grief and the expert Marie Curie care Helen received, you can listen to the full conversation below.

Helen and I met on holiday in 1959. I was about 16 at the time. It was a holiday romance that built up to a long marriage. There was always a feeling that we were a unit – I hadn’t really realised that until after she’d died. That was a difficult thing: there was half of your life gone.

I still say, ‘We’ve got in our garden…’, ‘We have two grandchildren…’ as though she’s still here. I still use the ‘we’. I find it almost impossible to say, ‘I am...’

She’d been in pain for about five or six years following a knee replacement. There was some nerve pain that kept going, which reduced her ability to get about and enjoy life.

Then a number of different things were diagnosed. She had some problems with her heart. The gradual withdrawal from life was something I think she found very, very difficult; she was a gregarious person and full of fun. In the end, she was diagnosed with kidney failure. Then she got pneumonia and we went into hospital. We had a pretty bad experience there.

“She couldn’t have had better last days”

We got her a place at a Marie Curie Hospice. It was just so completely wonderful, and changed our feelings . She was so well looked after there. It’s partly little things, at the hospice, that they allowed visitors in at almost any time. Helen’s grandchildren, who were then five and three, were allowed to come in. We were all around her bedside.

She couldn’t have had a better last few days of her life. She was happier than I’d seen her for six years, to be honest.

“Grief is like a battlefield”

The worst part of my grief, really, was knowing that Helen wouldn’t come back. I don’t know if it’s a common thing, but you kind of think, “Well, I haven’t seen her for a bit, but she’ll probably be back, because the house is the same, where she sits is the same, I’m making the same sort of food. She must walk in.” It’s probably ridiculous but those were the moments when I really felt the deepest grief, knowing that it would be forever.

We went on holiday in France three months after she’d died. My daughter was there as well. Someone had dropped a cup or it broke, or something like that, I just comforted her and the two of us had ended up in floods of tears. Those things come out every now and then, but that’s great. I’m glad there’s no absolute pattern to it. It’s all individual, it’s all about you.

I wrote in my diary that regret and loss are like dodging fire on a battlefield: one moment you’re okay then suddenly right in front of you something comes up, someone says something or you’re asked something by someone who doesn’t know she’s died. That’s always difficult.

I went into Camden Registry Office to register Helen’s death – that’s another bit of paper you have to have. There was a couple next to me, and they had a really tiny baby slung about the man’s chest, with a tiny little face. I thought this is just wonderful. One’s going out, leaving room for another one. We exchanged addresses and we still keep in touch. I think of Clara, the little girl, not as an embodiment of Helen but sort of as the one that took her place. I’d love to have told Helen about meeting this couple with the little baby. She’d have loved that.

“Show your emotions. Let it out.”

I can remember when I was young, my grandparents’ deaths were all mysterious. We weren’t invited to the funeral, it was something you shouldn’t see. I feel really glad that all my grandchildren were able to participate, see and understand, right up to the last minute, that this is what happens. You get ill, eventually your body stops working and that’s it. They know about that, and they can ask any questions. I really encouraged it afterwards. “Grandpa, when will you die then?” That’s fine, really good, I really enjoy having those sorts of conversations.

“All you can hope for is a place like Marie Curie”

Even in the most careful of circumstances where you say, “I’m going to deal with death, I know what to do,” you don’t at all. You absolutely don’t know. It sucker punches you. You don’t know what’s going to happen, how you’re going to feel or how you’re going to act. That’s the thing that struck me most of all: it’s different for everybody. And all you can hope for is that there is a chance, like Helen, to find a place like Marie Curie and be treated so wonderfully there, so the last days are not the worst days but the best days.

Listen now

This article is adapted from Michael's conversation in our podcast, On the Marie Curie Couch. To listen to the full episode, tap the Acast player at the top of the page or listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also watch a subtitled version on YouTube.

If you need support with bereavement or grief, call the Marie Curie Support Line on 0800 090 2309 or visit mariecurie.org.uk/information